Archive Record

Images

Metadata

Object ID |

2023.22.2 |

Object Name |

Video Recording |

Title |

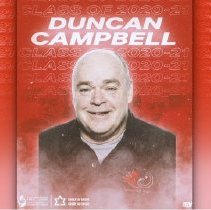

Duncan Campbell Interview |

Scope & Content |

Duncan Campbell interview, 2021. Born digital MP4, total viewing time 00:10:49. Transcript: Sean Reynolds: Duncan, I want to thank you for taking the time to chat with me here today and the most pressing question that I have I'll take right off the top. What's it like going through life with a sweet nickname like the Quadfather? Duncan Campbell: Well, I used to hate it to be honest, because I got it really early when I was nowhere near being a grandfather or any of those kinds of things. And now it's kind of cool at this point, and I'm actually a father now, so it's kind of cool. It was interesting, and it came really early, which was unusual I guess. But I've always just been involved in this game. This game has been my life basically. Sean Reynolds: Well, tell me about the roots of wheelchair rugby. How it started and why you felt the need to start a game of this nature. Duncan Campbell: Well, it was the time that affected it drastically in that I was already involved in sport, but it was all individual sports. It was more of a social sport thing than anything else at that time, way back. Hey, that was 40 years ago. And there was four of us that trained once a week. We lifted weights in the gym at the rehab center. And we had a volunteer that came and got the weights down for us. And one night that volunteer couldn't make it and we didn't know until we were already there. So we went in the gym. The gym was just down the hall, and we started throwing things around. And I was always at a rink rat. I grew up in Winnipeg. I was a rink rat. I loved team sports, and I loved hockey, and I played baseball, and I never did any of the individual sports when I was growing up. And we started playing around and we came up with this game that we ... It just happened. We tried a bunch of different things. It was all started based off basketball because that was the only wheelchair team sport that was available at the time. So we tried using garbage cans and finally we came down to this, "Well, let's quit trying to throw something in something. Let's just go across a goal line like rugby." And there was a guy in our group, an older guy, because you got to remember, I was only 19 at this time. Jerry Turwin, who knew all the admin people in wheelchair sports and that kind of thing. He did the sort of groundwork to get it demoed and we knew we had something good. We knew we had it, and we created a system so that everybody got to play to ensure that all levels of the type of disability that we have have a role on the floor and have to play. So it worked out really, really well. It took a few years. We talk about like it happened in the snap of a finger, but it took a few years to get it going, and then it took a few more years to expand it. Sean Reynolds: Well, you touched on something I found was really interesting. The classification system that you use to grade the players and get different players of varying abilities on the floor. I mean, the root of that is getting more and more people involved in making this sport accessible and never putting up barriers and saying, "This sport is not for you." Tell me about the drive to create that system and how that started and how you developed that. Duncan Campbell: Well, I think we started it right off the bat because we didn't want anybody that was a quadriplegic that could wheel a manual chair to be excluded from the game. So we created this system. And at that time, it wasn't what it is now. It's changed tremendously over time, but it still has the same philosophical base. So it still does the job that it was intended to do, but it's much more refined now and much more detailed. Back then, it was just we had these three categories of players and you had to have one of them, two of them, one of them, and you could mix them up a little bit. I can't even remember how it worked, but it ensured that everybody had a role on the floor and got to play. Sean Reynolds: For me, the first time I was introduced to the sport was the documentary Murderball, and this is years ago in the early 2000s that this came out. And I remember watching it. Great documentary. You and I were talking a little bit. You think it does a pretty good job of representing the sport. When I watched it for the first time, what really struck me was the violent physicality of the game at times, but also that you could sense that there was something cathartic for the players involved about that violent physicality. Explain that to me. What would be so cathartic about that? Duncan Campbell: I don't know. I know that we ensured that hitting was in the game because of our hockey roots mostly, but also a public perception of quadriplegia, which is a very health oriented, fragile. People perceive us as fragile. We can't do things like that. So when you can, you feel good about it, and you want people to know, "Hey, I'm not fragile. I'm not going to break when somebody hits me, and I'm going to hit somebody back." Sean Reynolds: What do you think it is about the sport when you take a look at all the time that you've spent in it, what do you think it is about the sport that resonates as widely as it does? Not just in the Paralympic community, but everywhere? In the general community, everywhere? Why does this sport resonate so much? Duncan Campbell: Well, I think because it's easy to understand. It's a pretty easy game to understand. It does have the physical component, which a lot of people really enjoy and respect in a way, and it's a lot of fun, and the games, in a lot of cases are really close. And it creates, and it provides everything that sport fans are looking for. It provides everything. It's got the social aspect to it. It's got the close games. It's got the rivalries. All those things are there. And I think also that we're not professional athletes. We're not paid to do what we do. So to get to where we get in terms of the Olympics now, the Paralympics now, and these guys have to train for hours and hours on end. The fact that we do that without getting paid, I think resonates with the public. Sean Reynolds: There's a point in that documentary we were talking about where one of the characters says, "I've done far more in my life in this chair because of this sport than I did when I wasn't in this chair." How common of a story was that for you? How often did you hear that? Duncan Campbell: Oh, it's huge. That's one of the things that I am proud about with that sport, is it has helped hundreds and well probably thousands of individuals do more with their lives than they thought they could because of this sport and because of the atmosphere around the sport. Guys help each other out. A new guy comes and he thinks he can't drive, and he thinks he can't get in and out of a bathtub, but these guys, everybody shows him how to do it, and all of a sudden they realize, "Whoa, I can do all these things." It's huge. Sean Reynolds: I can tell just in you talking about this that there's a lot of emotions tied up in these kind of moments. How rewarding has this been for you to have made this kind of difference through something that you've created, to make that kind of difference in the lives of so many people? Duncan Campbell: Well, that's kind of surreal. I don't really feel it on a day-to-day basis and just, well, now, four years ago, my wife and I decided, well, about 10 years ago, but it happened four or five years ago. We decided we were going to have kids. So my life is consumed now with a five-year-old and a three-year old. They're relentless. But it's a big, big thing. It's pretty cool. I wish the other three, other four guys that were involved got a little more of the accolades as well, but they didn't stay in the sport. Sean Reynolds: Yeah. Well, you're talking about accolades. You've earned so many accolades yourself. You're the first inductee into the International Wheelchair Rugby Federation. The Canadian Championship is named the Campbell Cup. What does it mean to be inducted into Canada's Sports Hall of Fame? Duncan Campbell: It's pretty cool. It indicates the same respect as able-bodied sport builders and sport participants get, which is a big, big thing. I'm in the same ... Hang on a sec. I'm in going to be in the same hall of fame as Wayne Gretzky. That's cool. Sean Reynolds: It's cool, and it's unbelievably deserved. Duncan Campbell: Thank you. Sean Reynolds: Anything else that you'd like to add? I mean, a moment like this deserves a chance to say what you want. The floor is yours. Anything you'd like to add? Duncan Campbell: Again, I hope that all the other guys and people that contributed to making this game as good as it is, realize what they did. Sean Reynolds: Duncan, I really appreciate your time and just a massive congratulations to you, and thank you for all that you've done for sport, not only in our country, but across the world. Thank you so much. Duncan Campbell: Thank you. Sean Reynolds: Congratulations. |

People |

Campbell, Duncan |

Search Terms |

Duncan Campbell Wheelchair Rugby Murderball Paralympic Games Para sport Para athlete DEI Diversity Equity Inclusion Campbell Cup |

bil.png)